Tharammel Peethambaran v. T. Ushakrishnan 2026 INSC 134 - Secondary Evidence - Photostat - CPC - Second Appeal - Finding Of Facts

Indian Evidence Act 1872 - Section 65 -Primary evidence is the rule, while secondary evidence is an exception admissible only in the absence of primary evidence. A party is generally required to produce the best evidence available; so long as the superior evidence (the original) is within a party's possession or reach, they cannot introduce inferior proof (secondary evidence). (Para 20.1) - The introduction of secondary evidence is a two-step process, wherein, first, the party must establish the legal right to lead secondary evidence, and second, they must prove the contents of the documents through that evidence. The twin requirements are conjunctive (Para 21) -There is no requirement that an application must be filed to lead secondary evidence. While a party may choose to file such an application, secondary evidence cannot be ousted solely because no application was filed. It is sufficient if the party lays the necessary factual foundation for leading secondary evidence either in the pleadings or during the course of evidence. (Para 20.7)

Indian Evidence Act 1872 - Section 85- In the absence of an original or at least a secondary evidence, it is impermissible to apply Section 85 of the Indian Evidence Act to conclude the execution of document - A photocopy of a document is no evidence unless the same is proved by following the procedure set out. (Para 23)

Indian Evidence Act 1872 - Courts should not by itself compare disputed signatures without the assistance of any expert, when the signatures with which the disputed signatures compared, are themselves not the admitted signatures. (Para 23)

Code of Civil Procedure 1908 - Section 100,103 - Second Appeal - The general rule is that findings of fact recorded by the trial and appellate courts are binding and will not be disturbed, even if they appear to be erroneous- However, this restriction is not absolute. Where the findings of fact are founded on assumptions, conjectures or surmises, or suffer from the vice of perversity, the High Court is well within its jurisdiction to interfere with findings of fact. The legality of a finding of fact, when challenged on the ground of perversity, itself constitutes a question of law and, therefore, may give rise to a substantial question of law under Section 100. finding may be termed perverse where it is arrived at by ignoring or excluding relevant and material evidence, by considering irrelevant material, or where it is based on no evidence or on wholly unreliable evidence. A decision based on no evidence is not confined to cases of complete absence of evidence, but also includes cases where the evidence on record, taken as a whole, is incapable of reasonably supporting the findings recorded. A finding that outrageously defies logic, suffers from irrationality, or is such that no reasonable person acting judicially could have arrived at it, is equally perverse in the eye of the law. Findings resting on the ipse dixit of the court or on conjecture and surmises reflect non-application of mind and stand vitiated on that ground as well - Insofar as documentary evidence is concerned, an inference drawn from the contents of a document is ordinarily a question of fact. However, the legal effect of a document's terms, its construction involving the application of legal principles, or a misconstruction thereof gives rise to a question of law (Para 16) The power under Section 103 CPC can be exercised only in exceptional circumstances and with circumspection. Before invoking this provision, the High Court must record a clear finding that the findings of fact recorded by the courts below are vitiated by perversity. In the absence of such a categorical finding, the exercise of power under Section 103 would fall outside the permissible limits of Section 100 of the CPC. (Para 16.7)

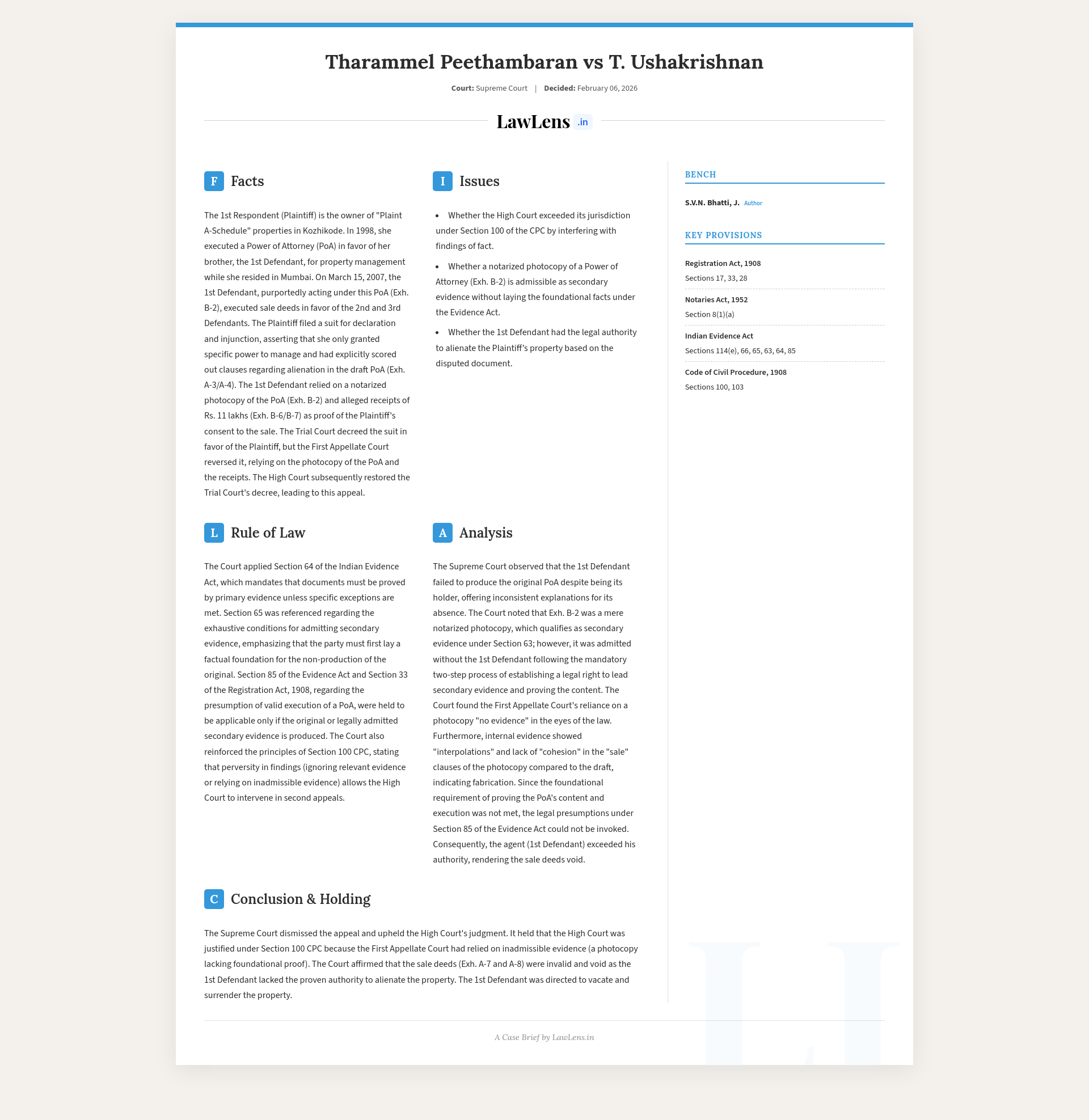

Case Info

Case name and neutral citationTharammel Peethambaran and Another v. T. Ushakrishnan and Another, 2026 INSC 134

CoramJustice Pankaj MithalJustice S.V.N. Bhatti (author of the judgment)

Judgment date06 February 2026 (New Delhi)

Case laws and citations referred

- Ramathal v. Maruthathal, (2018) 18 SCC 303

- Jagdish Singh v. Natthu Singh, (1992) 1 SCC 647

- Dinesh Kumar v. Yusuf Ali, (2010) 12 SCC 740

- Bharatha Matha v. R. Vijaya Renganathan, (2010) 11 SCC 483

- Hero Vinoth v. Seshammal, (2006) 5 SCC 545

- Sitaramji Badwaik v. Bisaram, (2021) 15 SCC 234

- Municipal Committee, Hoshiarpur v. Punjab SEB, (2010) 13 SCC 216

- Jagmail Singh v. Karamjit Singh, (2020) 5 SCC 178

- Smt. J. Yashoda v. K. Shobha Rani, (2007) 5 SCC 730

- Kaliya v. State of Madhya Pradesh, (2013) 10 SCC 758

- H. Siddiqui (D) by LRs v. A. Ramalingam, AIR 2011 SC 1492

- Ashok Dulichand v. Madahavlal Dube, (1975) 4 SCC 664

- Chandra v. M. Thangamuthu, (2010) 9 SCC 712

- Rakesh Mohindra v. Anita Beri, (2016) 16 SCC 483

- Dhanpat v. Sheo Ram, (2020) 16 SCC 209

- O. Bharathan v. K. Sudhakarana, (1996) 2 SCC 704

Statutes / laws referred

- Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 – Sections 100 and 103

- Indian Evidence Act, 1872 – Sections 63, 64, 65, 66, 85, 114(e)

- Registration Act, 1908 – Sections 17, 28, 33

- Notaries Act, 1952 – Section 8(1)(a)

- Benami Transactions (Prohibition) Act, 1988

Brief summary (three sentences)The dispute turned on whether the first defendant held a valid power of attorney authorising him to sell the plaintiff’s immovable properties, based only on a notarised photocopy (Exh. B-2) treated as a PoA. The Supreme Court held that Exh. B‑2 was merely secondary evidence, that no proper foundational facts under Sections 63–65 of the Evidence Act had been laid, and that the first appellate court had wrongly relied on this inadmissible photocopy to infer an authority to sell. Treating the appellate findings as based on “no evidence” and misreading of law, the Court upheld the High Court’s restoration of the trial court decree declaring the sale deeds void and dismissing the appeal.