Annamalai vs Vasanthi, 2025 INSC 1267 - Specific Relief Act - Breach Of Contract - Declaratory Relief

Specific Relief Act 1963 - Section 34 ; Indian Contract Act, 1872 - Ordinarily, for a breach of contract, a party aggrieved by the breach i.e., failure on the part of the other party to perform its part under the contract can claim compensation or damages by accepting the breach as a termination of the contract, or/ and, in certain cases, obtain specific performance by not recognizing the breach as termination of the contract . In a case where the contract between the parties confers a right on a party to the contract to unilaterally terminate the contract in certain circumstances, and the contract is terminated exercising that right, a mere suit for specific performance without seeking a declaration that such termination is invalid may not be maintainable. This is so, because a doubt /cloud on subsistence of the contract is created which needs to be cleared before grant of a decree enforcing contractual obligations of the parties to the contract - a declaratory relief would be required where a doubt or a cloud is there on the right of the plaintiff and grant of relief to the plaintiff is dependent on removal of that doubt or cloud. However, whether there is a doubt or cloud on the right of the plaintiff to seek consequential relief, the same is to be determined on the facts of each case. For example, a contract may give right to the parties, or any one of the parties, to terminate the contract on existence of certain conditions. In terms thereof, the contract is terminated, a doubt over subsistence of the contract is created and, therefore, without seeking a declaration that termination is bad in law, a decree for specific performance may not be available. However, where there is no such right conferred on any party to terminate the contract, or the right so conferred is waived, yet the contract is terminated unilaterally, such termination may be taken as a breach of contract by repudiation and the party aggrieved may, by treating the contract as subsisting, sue for specific performance without seeking a declaratory relief qua validity of such termination. (Para 27- 33)

Specific Relief Act 1963 - Section 16 - an opinion regarding plaintiff’s readiness and willingness to perform its part under the contract is to be formed on the entirety of proven facts and circumstances of a case including conduct of the parties. The test is that the person claiming performance must satisfy conscience of the court that he has treated the contract subsisting with preparedness to fulfil his obligation and accept performance when the time for performance arrives - Generally, time is presumed not to be the essence of the contract relating to immovable property. Therefore, onus to plead and prove that time was the essence of the contract is on the person alleging it. In cases where notice is given treating time as the essence of the contract, it is duty of the court to examine the real intention of the party giving such notice by looking at the facts and circumstances of each case. (Para 18-20)

Specific Relief Act 1963 - 2018 amendment -In Katta Sujatha Reddy v. Siddamsetty Infra Projects (P) Ltd.14, it was held that 2018 Amendment to the 1963 Act is prospective and cannot apply to those transactions that took place prior to its coming into force- This decision was reviewed and recalled in Siddamsetty Infra Projects (P) Ltd. v. Katta Sujatha Reddy but in the review order/ judgment this Court did not specifically hold that the amended provisions would govern suits instituted prior to the 2018 Amendment Rather, in review, this Court proceeded to decide the matter by assuming that the grant of specific performance continued to be discretionary to a suit instituted before the date of the amendment. (Para 34)

Specific Relief Act 1963 - Section 31,34 -A declaratory relief seeks to clear what is doubtful, and which is necessary to make it clear. If there is a doubt on the right of a plaintiff, and without the doubt being cleared no further relief can be granted, a declaratory relief becomes essential because without such a declaration the consequential relief may not be available to the plaintiff8. For example, a doubt as to plaintiff’s title to a property may arise because of existence of an instrument relating to that property. If plaintiff is privy to that instrument, Section 31 of Specific Relief Act, 1963 enables him to institute a suit for cancellation of the instrument which may be void or voidable qua him. If plaintiff is not privy to the instrument, he may seek a declaration that the same is void or does not affect his rights. When a document is void ab initio, a decree for setting aside the same is not necessary as the same is non est in the eye of law, being a nullity. Therefore, in such a case, if plaintiff is in possession of the property which is subject matter of such a void instrument, he may seek a declaration that the instrument is not binding on him. However, if he is not in possession, he may sue for possession and the limitation period applicable would be that as applicable under Article 65 of the Limitation Act, 1963 on a suit for possession. Rationale of the aforesaid principle is that a void instrument /transaction can be ignored by a court while granting the main relief based on a subsisting right. But, where the plaintiff’s right falls under a cloud, then a declaration affirming the right of the plaintiff may be necessary for grant of a consequential relief. However, whether such a declaration is required for the consequential relief sought is to be assessed on a case-to-case basis, dependent on its facts. (Para 25)

Maintainability - Though a plea regarding maintainability of the suit, even if not raised in written statement, may be raised in appeal, particularly when no new facts or evidence is required to address the same.

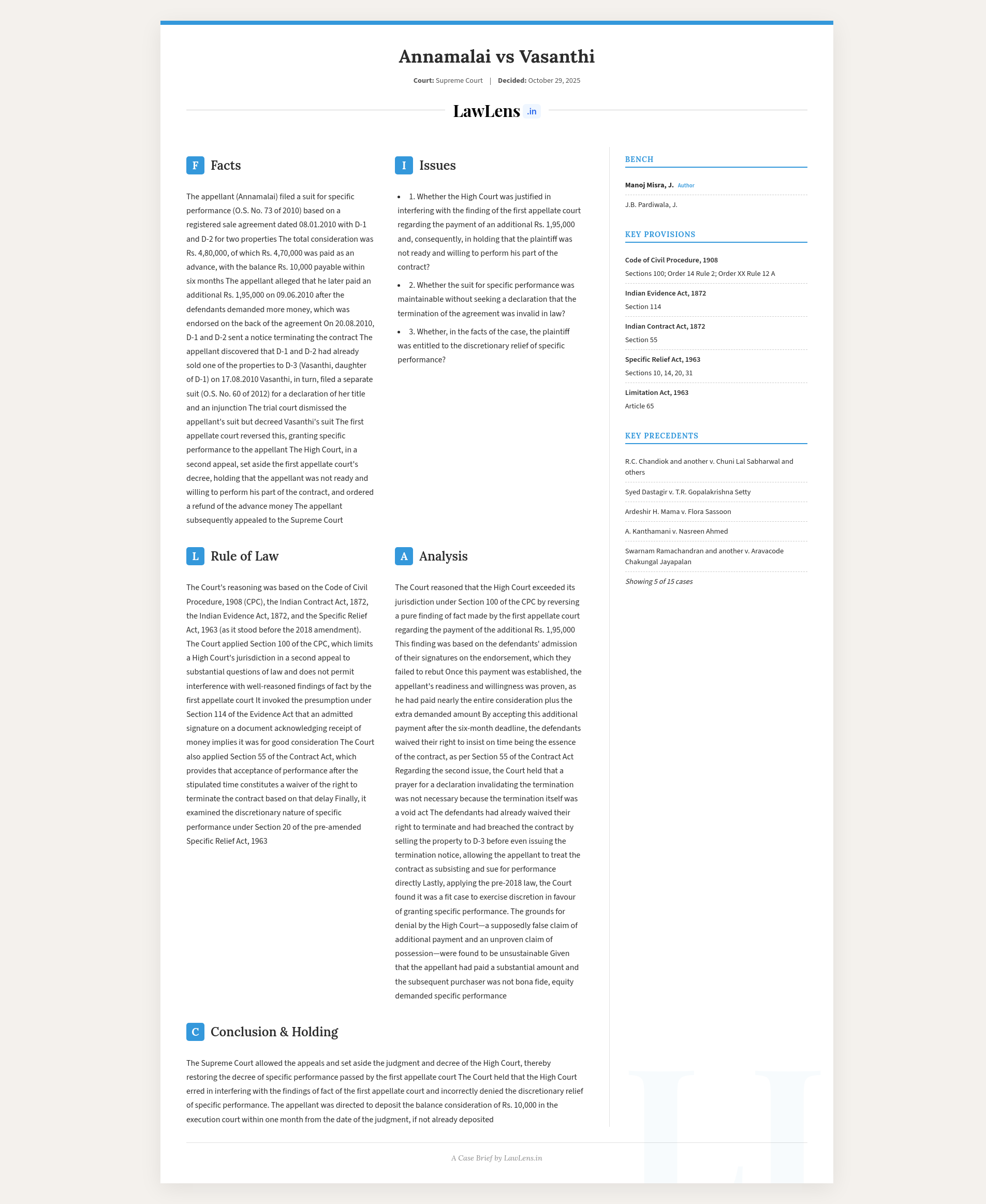

Case Info

- Case name: Annamalai vs Vasanthi and Others.

- Neutral citation: 2025 INSC 1267.

- Coram: Justices J.B. Pardiwala and Manoj Misra.

- Judgment date: October 29, 2025.

Case laws and citations

- R.C. Chandiok v. Chuni Lal Sabharwal, (1970) 3 SCC 140.

- Syed Dastagir v. T.R. Gopalakrishna Setty, (1999) 6 SCC 337.

- Ardeshir H. Mama v. Flora Sassoon, AIR 1928 PC 208 = 1928 SCC OnLine PC 43.

- Swarnam Ramachandran v. Aravacode C. Jayapalan, (2004) 8 SCC 689.

- I.S. Sikandar v. K. Subramani, (2013) 15 SCC 27.

- A. Kanthamani v. Nasreen Ahmed, (2017) 4 SCC 654.

- Katta Sujatha Reddy v. Siddamsetty Infra Projects (P) Ltd., (2023) 1 SCC 355.

- Siddamsetty Infra Projects (P) Ltd. v. Katta Sujatha Reddy, 2024 INSC 861 = 2024 SCC OnLine SC 3214.

- OPG Power Generation Pvt. Ltd. v. Enexio Power Cooling Solutions India Pvt. Ltd., (2025) 2 SCC 417.

- R. Kandasamy (since dead) v. T.R.K. Sarawathy, (2025) 3 SCC 513.

- Prem Singh v. Birbal, (2006) 5 SCC 353.

- Shanti Devi (deceased) through LRs v. Jagan Devi, 2025 SCC OnLine SC 1961.

- Ravinder Singh v. Sukhbir Singh, (2013) 9 SCC 245.

- Babu Lal v. Hazari Lal Kishori Lal, (1982) 1 SCC 525.

- Anson’s Law of Contract (29th Oxford Edn.) – quoted on forms of breach.

Statutes and provisions referred

- Code of Civil Procedure, 1908: Section 100; Order XX Rule 12A.

- Indian Evidence Act, 1872: Section 114 with Illustration (c).

- Indian Contract Act, 1872: Section 55 (effect of accepting performance at a different time).

- Specific Relief Act, 1963: Sections 10, 14, 20 (pre-2018); Section 31.

- Limitation Act, 1963: Article 65.

Is the suit for specific performance of a contract in teeth of termination of the contract maintainable without seeking a declaration ?#SupremeCourt discusses this issue here: https://t.co/2iTYMVMJAW pic.twitter.com/bq6HbjtaZ1

— CiteCase 🇮🇳 (@CiteCase) October 29, 2025

#Supreme Court holds that even if a plea regarding maintainability of the suit was not raised in written statement, it can be raised in appeal, particularly when no new facts or evidence is required to address the same. https://t.co/2iTYMVMJAW pic.twitter.com/LZQU9UJ97X

— CiteCase 🇮🇳 (@CiteCase) October 29, 2025

#SupremeCourt clarified that in its Siddamsetty judgment, it did not specifically hold that the 2018 amendment of Specific Relief Act would govern suits instituted prior to it. https://t.co/2iTYMVMJAW pic.twitter.com/xqvjyeiHVG

— CiteCase 🇮🇳 (@CiteCase) October 29, 2025