Union of India & Ors. v. Alok Kumar 2025 INSC 1091 - Recruitment - Appointment

Service Law - Recruitment and Appointment - Quoted from Prafulla Kumar Swain v. Prakash Chandra Misra :The term “recruitment” connotes and clearly signifies enlistment, acceptance, selection or approval for appointment. Certainly, this is not actual appointment or posting in service. In contradistinction the word “appointment” means an actual act of posting a person to a particular office - Recruitment is just an initial process. That may lead to eventual appointment in the service. But, that cannot tantamount to an appointment. (Para 21)

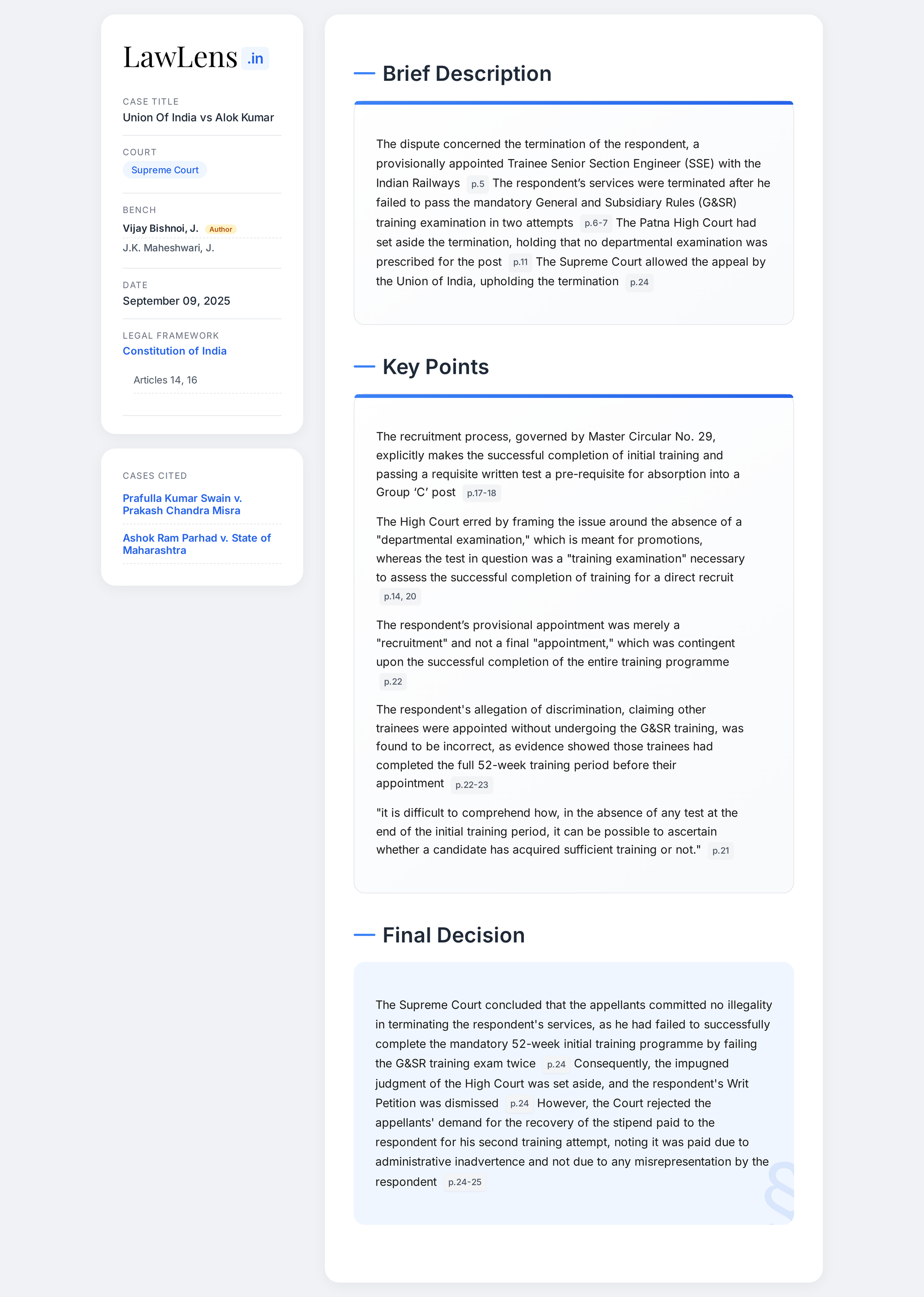

Case Info

The case is

Case Name and Neutral Citation

- Case Name: Union of India & Ors. v. Alok Kumar

- Neutral Citation: 2025 INSC 1091

Coram (Judges)

- Justice J.K. Maheshwari

- Justice Vijay Bishnoi

Judgment Date

- Date: 09th September, 2025

Caselaws and Citations

- Prafulla Kumar Swain v. Prakash Chandra Misra, (1993) Supp (3) SCC 181

- Quoted for the distinction between “recruitment” and “appointment”.

- Ashok Ram Parhad v. State of Maharashtra, (2023) 18 SCC 768

- Followed the above principle.

Statutes / Laws / Circulars Referred

- Master Circular No. 29 dated 28.06.1991 (Governing recruitment of Group ‘C’ non-gazetted posts in Railways)

- Indian Railway Establishment Manual, 1989 (Definitions and training requirements)

- Centralized Employment Notice No. 02/2014 dated 20.09.2014 (Recruitment advertisement)

- RBE No. 11/2010 dated 15.01.2010 (Revised Training Module for SSEs)

- Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution of India (Equality and non-discrimination in public employment)

Q&A

Q&A on Union of India & Ors. v. Alok Kumar, 2025 INSC 1091

Below is a comprehensive set of questions and answers spanning facts, procedure, issues, legal principles, reasoning, holdings, and implications, with emphasis on the legal aspects.

1) What is the case about?

- This case concerns the termination of a directly recruited Senior Section Engineer (SSE) trainee in the Railways for failing the mandatory written test (G&SR) at the end of training, and whether such termination was lawful under the governing rules.

2) Who decided the case and when?

- The Supreme Court of India, per Justices J.K. Maheshwari and Vijay Bishnoi, on 09 September 2025 (Neutral citation: 2025 INSC 1091). It is a non-reportable judgment.

3) What is the procedural history?

- The trainee’s services were terminated on 04.01.2019 after failing the G&SR test twice. The Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT), Patna, dismissed his challenge. The Patna High Court allowed his writ petition, set aside the termination and directed benefits. The Union of India appealed to the Supreme Court, which set aside the High Court’s judgment and restored the termination (but disallowed stipend recovery).

4) What were the key facts relevant to the legal dispute?

- The Railway Recruitment Board (RRB) issued Employment Notice No. 02/2014 for SSEs, stating selected candidates must undergo training where prescribed.

- The Master Circular No. 29 (28.06.1991) requires a written test at the end of initial training for Group ‘C’ direct recruits; retention depends on passing.

- The Indian Railway Establishment Manual (1989) defines “trainee” and provides SSE training duration as 52 weeks.

- The respondent completed 46 weeks, then underwent a 3-week G&SR course at ZRTI; he failed the written test twice.

- He was on a two-year probation; appointment letter warned that unsatisfactory performance during training could lead to termination.

- He was asked to refund Rs. 1,53,354 stipend erroneously paid for the second attempt, despite the rule that OBC trainees get a second attempt without stipend.

5) What was the core legal issue framed by the High Court?

- Whether the petitioner (trainee SSE) is required to pass any prescribed departmental examination for the post of SSE to gain permanent status.

6) What were the Union’s (Appellants’) legal arguments?

- The Master Circular mandates a written test at the end of initial training; retention depends on passing it.

- “Training examinations” (not “departmental examinations”) are inherent to completion of training; departmental exams are for promotions, not direct recruits.

- Employment Notice and provisional appointment letter warned about training and consequences of failure.

- The Revised Training Module (RBE No. 11/2010) organizes the 52-week training but does not displace the Master Circular’s mandate of a written test.

7) What were the Respondent’s legal arguments?

- No departmental examination is prescribed for SSEs; the Revised Training Module does not mention such a requirement.

- He completed 46 weeks and alleged discriminatory treatment because some similarly placed trainees allegedly received permanent posting without G&SR training.

- Termination violated Articles 14 and 16 (arbitrariness and unequal treatment).

8) What legal materials governed the dispute?

- Master Circular No. 29 (28.06.1991) – requires written qualifying test after initial training and warns of retention being contingent on passing.

- Indian Railway Establishment Manual, 1989 – defines trainee/apprentice; specifies SSE training duration (52 weeks); allows Zonal Railways to set training details.

- RBE No. 11/2010 (15.01.2010) – Revised Training Module for the 52-week programme.

- Employment Notice No. 02/2014 – stipulates training “wherever prescribed.”

- Provisional appointment letter – two-year probation; unsatisfactory training performance may lead to termination.

9) How did the Supreme Court treat the distinction between “departmental examination” and “training examination”?

- It held that the High Court erred by focusing on the absence of a “departmental examination.” For trainees, the relevant requirement is the “written training test” mandated by the Master Circular. Departmental exams pertain to promotions, not initial appointment of direct recruits.

10) What did the Court say about the applicability of the Master Circular vis-à-vis the Revised Training Module?

- The Master Circular governs recruitment and mandates the written test after initial training. The Revised Training Module structures the 52-week training but does not (and cannot) supersede the Master Circular’s requirement of a written qualifying test.

11) What is the legal significance of “recruitment” versus “appointment” here?

- Citing Prafulla Kumar Swain v. Prakash Chandra Misra, (1993) Supp (3) SCC 181 (followed in Ashok Ram Parhad v. State of Maharashtra, (2023) 18 SCC 768), the Court emphasized:

- Recruitment is the process of selection/acceptance for potential appointment.

- Appointment is the actual posting to the office.

- A trainee’s provisional engagement is part of recruitment; permanent appointment is conditional on successfully completing training and passing the test.

12) How did the Supreme Court address the Article 14/16 discrimination claim?

- It rejected the claim. The record showed multiple trainees underwent the same G&SR training and testing; most cleared it. Allegations that others received permanent posting after only 46 weeks were contradicted by RTI responses indicating those trainees completed the full 52 weeks. No hostile discrimination was established.

13) What standard did the Supreme Court apply to review the High Court’s interference with the CAT’s order?

- While not laying out an abstract standard, the Court effectively held that the High Court misapplied the governing rules by conflating departmental and training examinations and overlooking the Master Circular’s mandate. CAT’s factual and legal conclusions were sound; High Court’s interference was unwarranted.

14) What was decided about the recovery of stipend?

- Although the respondent was not entitled to stipend for the second attempt (OBC candidates get a second attempt without stipend), the Court refused recovery because the payment was due to administrative inadvertence and not fraud or misrepresentation by the trainee. Hence, recovery demand was quashed.

15) What is the final holding and relief?

- The appeal was allowed in part:

- High Court’s judgment set aside.

- Termination order upheld (writ petition dismissed).

- Recovery of erroneously paid stipend disallowed.

16) What practical rule emerges for Railways and trainees?

- For Group ‘C’ direct recruits (including SSEs), successful completion of the prescribed initial training and passing the written training test is a condition precedent to permanent appointment. Failure, even after permissible attempts, justifies termination during probation.

17) How does probation factor into the legality of termination?

- The provisional appointment explicitly placed the trainee on two-year probation and warned that unsatisfactory performance “in the field of training” could result in termination. Given the trainee failed the qualifying written training test twice, termination during probation was within the stipulated conditions and governing circulars.

18) Does the absence of an express test in the Revised Training Module negate the Master Circular requirement?

- No. The Module organizes training content/duration but does not remove the Master Circular’s requirement of a written qualifying test after initial training. The Court underscored the necessity of a test to ascertain sufficiency of training.

19) What facts undermined the Respondent’s assertions of arbitrariness?

- Multiple trainees underwent identical G&SR training; the overwhelming majority passed in the first or second attempt.

- RTI replies showed the comparators completed the full 52 weeks before permanent posting.

- There was no targeted, punitive, or exceptional treatment toward the respondent.